The Poly

24 Church St, Falmouth : 01326 319461

The Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society

What's On Calendar

Have a look at the calendar text here to see what's coming up.

THE CHARITY

The Poly is a thriving charity promoting engagement in the arts, sciences and Cornish history through film, live events, exhibitions, lectures and workshops, with our roots in artistic and technological innovation and local industry.

Our vision is to be a place where everyone feels welcome to be entertained, engage with culture, and be creative.

Our Mission, as a key cultural and community hub in Cornwall, is to provide inspiring, inclusive and innovative entertainment, learning and development opportunities across the arts, sciences and history.

Registered charity 1081199.

OUR HISTORY

OUR HISTORY

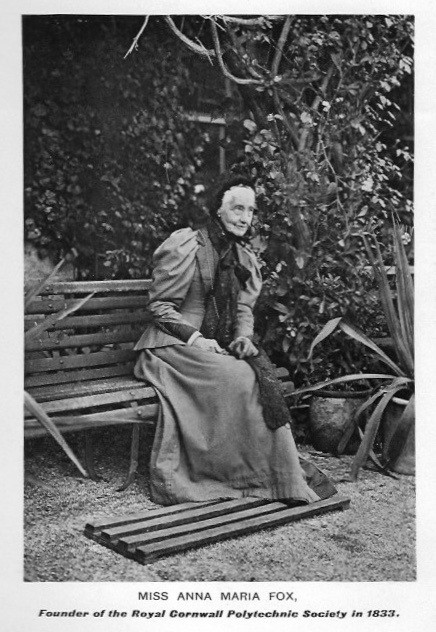

The Cornwall Polytechnic Society (the Poly) was founded in 1833, the inspiration of Anna Maria and Caroline, the teenage daughters of Robert Were Fox of G.C. Fox & Co, a prominent Falmouth firm of shipping agents. The firm was also joint owner of the Perran Foundry, whose workmen constantly brought models and inventions for inspection, and new ideas for improving the working of the foundry. With their father’s encouragement, a Society was formed ‘To promote the useful and fine arts, to encourage industry, and to elicit the ingenuity of a community distinguished for its mechanical skill’.

The Society was certainly founded on philanthropic principles, but President Sir Charles Lemon, seven prominent Cornish Vice Presidents, and Chairman Charles Fox, were all successful businessmen, for whom whatever ‘encouraged industry’ should also be good for business. With this in view, the founders determined that a large Hall should be erected by the Society to accommodate an annual exhibition of new inventions, especially mechanical ones, in an era when science was continually revealing new wonders to the world.

For the first two years, exhibitions were held in the Falmouth Classical School, which proved so popular, and were so overcrowded, that the Committee decided that the new Hall and permanent home for the Society should be built as soon as possible.

You can read more about the history of The Poly in the following books:

Founding The Poly describes the industrial conditions that called for the creation of the new society.

Cornwall's House of Inventions tells the story of those inventions and the Hall that was built to exhibit them and how The Poly ended up re-inventing itself.

PDF versions of those books can be found here:

Picture - Anna Maria Fox, Founder of the Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society.

Meet the Napoleonic 32nd Cornwall Regiment of Foot

Meet the 32nd Cornwall Regiment of Foot at The Poly. ...

Find out moreSwords, Swords, Swords

SWORDS, SWORDS, SWORDS- join the Swordstorian for an adventure into the world of swords- Knights, Pirates, Princess and...

Find out moreSpring Open: Open Call

Calling local artists! Enter your work into our annual curated art show. This exhibition is a celebration of the...

Find out more

Calendar

Calendar